The Changing

Shoreline

of New York City

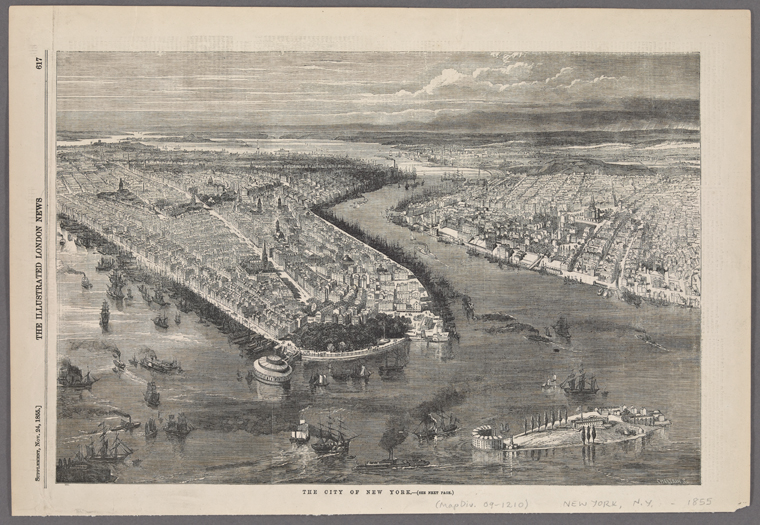

The Changing Shoreline of New York City surveys key points along New York City’s shoreline with a particular focus on Manhattan’s waterfront expansion. Historical maps of New York City juxtapose current coastal conditions of the city, revealing dramatic material landmass changes through time which are expressed through subtle contour differentiations mapped by a single line. The street grid of Manhattan, brought into effect by the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, provokes a hard edged condition insensitive to the many natural ecologies and layered boundaries that Manhattan island once hosted. The plan imposes efficiency and modernity onto the diverse landscape contained in the original outline of the earliest maps of Manhattan, usually obliterating the natural conditions when confronted with a diverse shoreline.

In an attempt to destabilize the perception of coastal boundaries in Manhattan today, the stories below trace minute accounts of a Manhattan that was in the process of radical transformations. The focus on water further shifts the city imaginary to explore a territory that has been consecutively filled-in, uprooted, and neglected in the expansion of the great metropolis. This guided tour outlines existing programs along the hardened shoreline, a brief history of the site and its past shoreline qualities, as well as future proposals for many of these sites which today face variable urban pressures due to changing climate conditions and urban revitalization developments.

Scroll down to explore how New York City’s shoreline changed throughout the centuries, and view maps from the New York Public Library’s collection of historical maps.

-

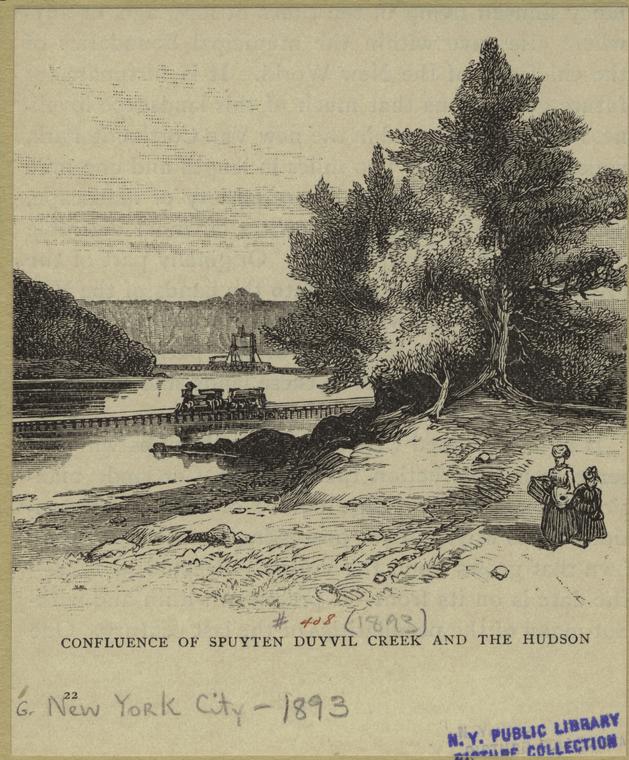

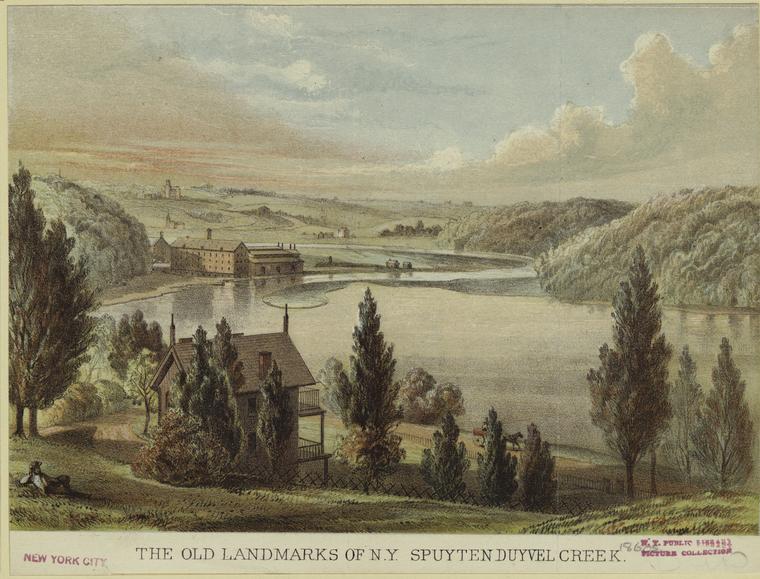

Spuyten Duyvil Creek, now the namesake of a shorefront park right across the Harlem River from Inwood Park, was a narrow, winding, noxious waterway with four tides per day which at the time only suggested that Manhattan was detached from mainland Bronx. In Dutch, the Spuyten Duyvil translates as the Spitting Devil so you can imagine the difficulty for the original settlers of the island to navigate their wide wooden ships to get from one side of the island to the other. The shoreline park is bounded by the Metro-North Rail which runs directly on the coast and makes its way into Grand Central from the station in 23 minutes.

Map: Atlas of the entire city of New York (1879), opacity:

-

Today, this part of Tibbett’s Brook flows under city streets as it was channeled underground in the late 18th century. Early on in New York history the brook would provide water and transportation to settlers along the edge of the water, however, as the population grew, the brook was seen as an obstacle. It was replaced by modern infrastructures and buried underground. Today, the brook resurfaces in Van Cortlandt Park and enters Van Cortlandt Lake. The lake was formed in 1699 when the Van Cortlandt estate built a dam to provide power for their sawmill, a popular form of economic growth in the 18th century. The park and lake today are the only remnants of native New York forestry that could have been found in the pre colonial era. Projects to daylight the brook, or expose the water to the aboveground, provide interesting prospects to connect city parks together and relieve the city sewer system of CSOs (Combined Sewage Overflow) during storms. The brook currently is streamlined with the sewer system and since the waterbody is alive and moving, it supplies an influx of water that is overwhelming to the wastewater treament infrastructure. This causes raw sewage to be expelled into the Harlem River on particularly rainy days and improper drainage for the park upstream.

-

Related to the Spuyten Duyvil Creek, Marble Hill played a role in the shaping of the northern tip of Manhattan as we know it today. The Harlem River Ship Canal, a massive vision that was bound to fulfill many ship-goers dreams, executed an awesome feat during the late 19th Century. The land mass of Marble Hill originally connected to the eastern most part of the northern tip of Manhattan, today where Columbia University Bakers Field is located and Broadway extends to the Bronx. The bulging appendage posed an obstacle for many maritime voyages as the Spuyten Duyvil Creek was already uncompromising enough. Finally with government support and a company’s work force, the Harlem River Ship Canal blasted through the crevice in 1895 that just barely joined Marble Hill with Manhattan and created a creek wide enough for ships to pass through from the Harlem River and onto the Hudson.

Marble Hill’s identity as an island was only temporary as it later joined the Bronx in 1913 by landfill of the original Spuyten Duyvil Creek using material from the excavation for the foundation for the Grand Central Terminal. The final phase to complete the vision for a passageway that would make the island fully possible to circumnavigate fused the peninsula that stuck out of the Bronx to Manhattan. The result forced Johnson Iron Works, a company town that produced steel mechanical parts on the peninsula and peaked in productivity and population around 1917, to shut down and the land was fused to supply Manhattan’s further expansion. The island was now fully independent as a land mass and a web of communication and transportation infrastructure progressively installed Manhattan’s site specificity. Marble Hill, now a part of the Bronx, is still technically part of Manhattan; its street names are a reminder of the founding Dutch colony that made its way as the first European settlement in the island and it is one of the only places in Manhattan, similar to the neighborhood of Spuyten Duyvil, where urban dwellers live in freestanding houses with porches and spacious gardens. Its winding roads reflect the former path the Spuyten Duyvil Creek established so long ago and is now imprinted into the city’s concrete fabric.

Map: Atlas of the Entire City of New York (1879), opacity:

-

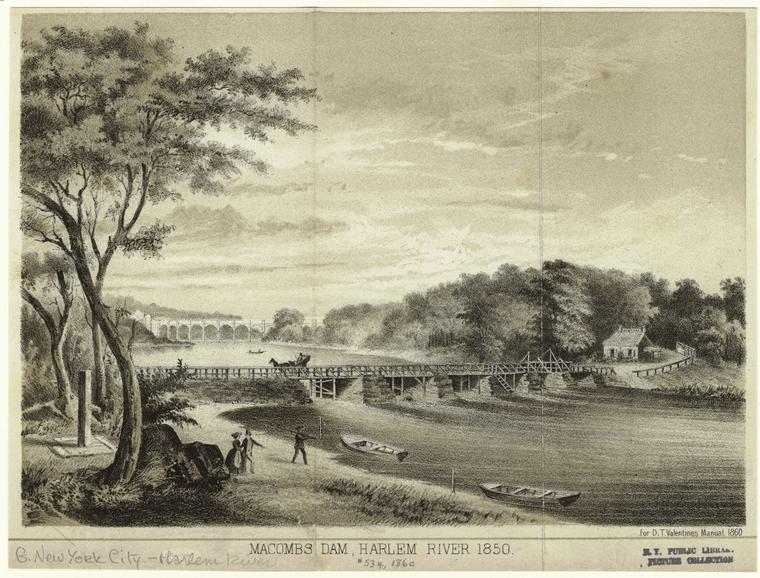

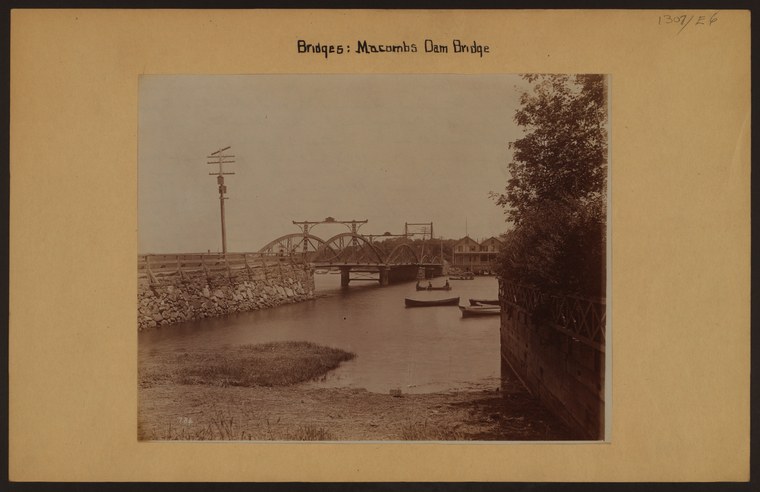

Cromwell’s Creek, completely filled in by modern infrastructure, used to flow south from Morris Heights in the inside of the Bronx into the Harlem River. At the confluence, tidal marshes marked the transition area between the Bronx and the Harlem River from a more terrestrial and hilly environment to that of the marshy wetland ecosystem in early New York history. The Creek is completely filled in today, with major parkland occupying the space where water used to flow. Gradually the waterbody was filled in for new development starting in the 1700s. Macombs Dam Bridge symbolically extends the flow of the now deceased creek and connects Manhattan to the Bronx at a very busy intersection which involves pedestrians, baseball spectators, vehicles, bicyclists, and residential blocks all coming together at once.

The largest baseball stadium, home to the Yankees, sits on the forgotten creek and is neighbor to Heritage Field where the first stadium was built in 1923. The migration of urban programs and their remnant footprints contrasts sharply with depletion of environmental ecosystems native to the site. One of the forgotten attractions that once linked the environment and recreation in harmony includes ice skating at Mill Pond. Filled in since the beginning of the 20th century, the pond was a bonus to the larger hydrological system sustained by the bloodline of Cromwell’s Creek and successfully organized communities around water.

-

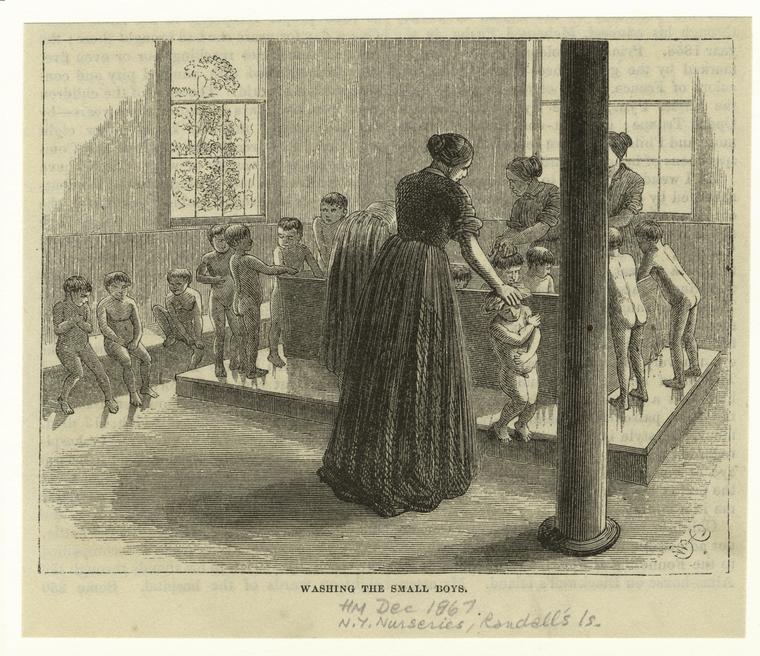

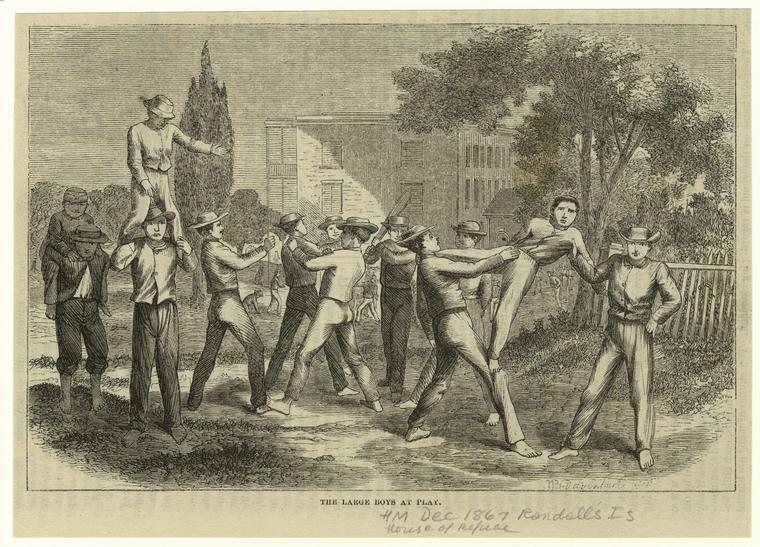

Similar to Roosevelt Island and North Brother Island, the city’s outcasts were quarantined outside of bustling lower Manhattan into remote concentrations of marginalized people on islands like Randall’s and Ward’s, often left unattended by the state and city during the 19th century. The overwhelming influx of immigrants and massive construction initiatives taken up by the city during this time made Randall’s and Ward’s Islands a designation for controlling populations and allowing unaccounted acts of neglect. Before the horrific maltreatment of New York City’s outcasts in the 19th century, Randall’s and Ward’s Islands were known as Little Barn and Big Barn islands, a misnomer of the British man who bought the property to profit from his business. The islands were separated from each other by a Sunken Meadow as well as from the greater Manhattan, which was still in the early 1800s mostly farmland and wild terrain.

Instituting massive change to the city fabric in the early 20th Century, Robert Moses, head of the Triborough Bridge Authority at the time, pushes negotiations to shut down the unjust hospitals and asylums and build a massive bridge project that links Manhattan, the Bronx, and Queens today. The site, historically a receptacle for unwanted people and occupations, reflects a tumultuous past and is itself fragmented in program, oddly partitioned to accommodate city operations closed off to the public and open space for public use. Although envisioned as a revitalized space for the community around the island, Randall’s and Ward’s is still out of reach in the city imaginary as the traffic to and from boroughs dominates provisional public access via footpaths and minimal bike lanes.

-

In 1695, colonial settlers stumble upon two companion islands in the East River comfortably nested between the southern Bronx coast and northern Queens limits. North Brother Island and definitely smaller South Brother Island remain relatively dormant under the ownership of the new residents who focus thier attention in developing the more busy areas of Manhattan and Brooklyn. Strong currents around the islands and the detached position from the emerging city diffuse the settlers’ initial interest with colonizing the site, although the networks for future expansion have already been established. In two hundred years, North Brother Island is activated as the city grows and requires more space to accomodate space for hospitals, public gardens, and finally an asylum for young drug addicts. Transferred from Blackwell’s Island in 1885, Riverside Hospital quarantines typhoid patients away from the city mass and engages in the city’s tradition of employing island land masses to detain unwanted immigrants and sick people. This first hospital sets the precedent for the island’s consequent regenerations as a place to store the city’s castaways, usually due to a lack of management of the population boom and immigrantion spike as well as the medical knowledge for taking care of patients with infectious diseases.

In the 1950s, when the city reclaims the island, Riverside Hospital accomodates a growing population of young people affected by a narcotics epidemic in New York City. Frank Lima, New York City poet born in Spanish Harlem, was a former patient in the rehabilitation program there and notes that the island “was one hell of an experience. We made up the laws and rules. It was a pathological zoo.” In the midst of all this chaos, Lima is encouraged to continue his poetry by fellow artist and mentor Sherman Drexler who would teach painting to the youth in the facility. Both figures are indicative of the larger art scene in New York City at the time and more peripherally the drug addictions that became popular within their circles and more widespread throughout the city. The island also reappears in a number of fictional literature works including Tennessee Williams’ Moise and the World of Reason and Evan Hunter’s short story Happy New Year, Herbie. The institution is abandonned in the 1960s. Today, the site is in architectural ruin, Riverside Hospital decaying and hollow, and only authorized personnel has access to the island. There also has been a recent decline in the number of wading birds spotted on the island, indicating an ecological shift in the New York City demography of birds.

-

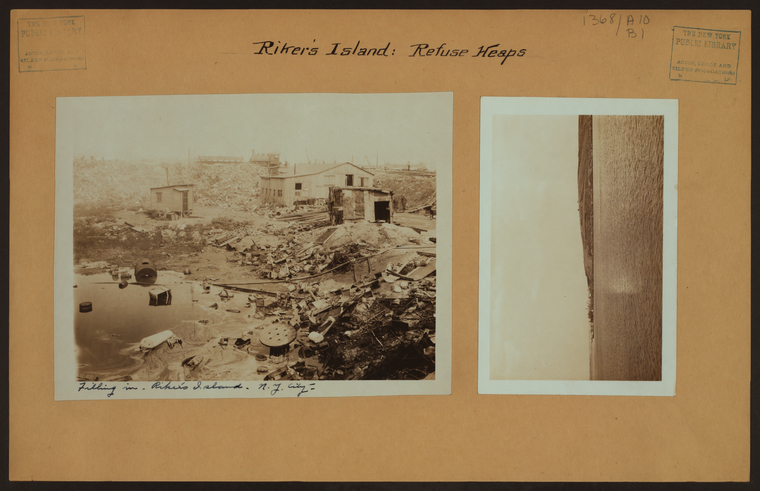

The facility reclaims around 400 acres to fit the current penitentiary, a modern iteration of the heyday at Blackwell’s Island. The name Rikers goes back to Dutch colonial times when the then current mayor Peter Stuyvesant granted the land to a family of farmers. The island sustained at least one household throughout its life as a colonial land appropriated from the native people of Manhattan, and was associated with Queens county until the city consolidated and is now under Bronx jurisdiction. Landfill was redirected to Rikers which ended New York’s ocean dumping that harmed Coney Island and New Jersey shores as well as construction debris from the city’s excavation of subway lines. Much of this labor to manage the site was carried out by prisoners of Rikers Island in the 1890s which at this time had basic prison facilities installed. The unstable natural state of the island (only half of its original acres reached above the high water mark, and about 7 times that figure was the island defined by a shallow sandbar) was constantly smoldering under the burden of the perpetual overcrowding in the correctional system as well as the dumping that took place to form the island.

Rikers Island perpetuates the corrupt treatment of prisoners as earlier island detention centers have established in the city’s history. As one of the last standing operations of this sort in the city, many actors are fighting to end the cycle of unjustified and inhuman imprisonment. There has been a push by the current mayor to shut down Rikers permanently and allies for the cause have been supportive to move forward. Restructuring the prison system will require careful planning and a new language to accomodate the incarcerated in society and provide meaningful resources for communities to heal and work together rather than subscribing to discriminatory practices of an insensitive justice system.

-

Like most native ecologies lost to urbanization in the city, neglected sites potentially can be transformed into park lands. Sunswick Creek originally flowed through Queens from present day Astoria towards Long Island City, severing this part of Queens into a distinct and ecologically diverse land mass or salt marshes and rich soils. Following the line of creek, industry would soon root itself within the footprint dilineated by hydrology and pervert the land’s innate logics and natural processes. Colonial sawmills were replaced by heavier industrial equipment which solidified the industrial atmosphere of the site. A major player in this setting was the Steinway Company town which emerged and took over most of the Astoria landscape.

Socrates Sculpture Park, located at the mouth of Sunswick Creek, resembles the community initiative inspired by artists Mark di Suvero along with Isamu Noguchi to restore the land for people to use. The park successfully uses space that has been in recent history frequently overlooked and underappreciated by the city due to the coarseness of its appearance as an unregulated and illegal dumping ground. Located in a low income community in the late 20th century, the status of the site during its most vulnerable time corrupted the image of the area and encouraged the illegal activity further. The community, in response to multiple calls of action by local activists, mobilzed to export the dump to somewhere else in order to restore the environment. Today, the neighborhood is booming with new residents and makers completely recontextualizing where the origins of the creek have come from.

-

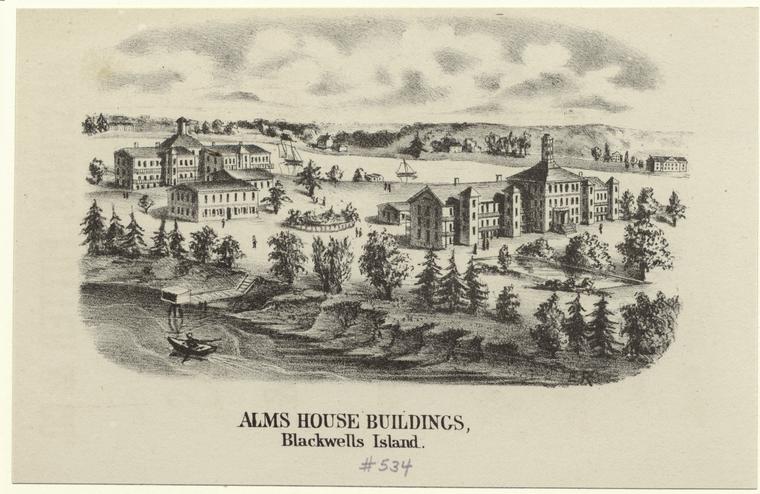

The City of New York excommunicates Roosevelt Island, originally land of the Lenape then turned farmland at the hands of the Dutch, for most of its history which seems contradictory to its comfortable suburban disposition within the context of the city. One of the only island communities outside of the massive Manhattan island, Roosevelt Island claims a shoreline all to itself, but it has not always been defined by scenic views and jogging couples. Insane asylums, hospitals, and penitentiaries dominated the landscape of the island during the time that Manhattan was expanding by the Commissioner’s Plan of 1811 and the population of immigrants in downtown Manhattan was exponentially growing. The corrective institutions were wildly untame, corrupted, and never functional as documented in the outstanding reports of young female journalist Nellie Bly. At one of the heights of its instability, Riverside Hospital needed to be moved to North Brother Island where it received the transferred patients from Blackwells Island.

In the question of its future under 20th Century governance, Roosevelt Island became a hotbed for architectural revival and expanded city planning, including the preservation of some of the original institutional buildings and urban green-space renewal. Today, the ruins of Blackwells Island dilapidate peripherally to the growing information center started by Cornell Tech as well as the open landscapes on the island, including Four Freedoms park designed by architect Louis Kahn. The site is more accessible and favorable to visit today and can be reached by tram, subway, and ferry.

-

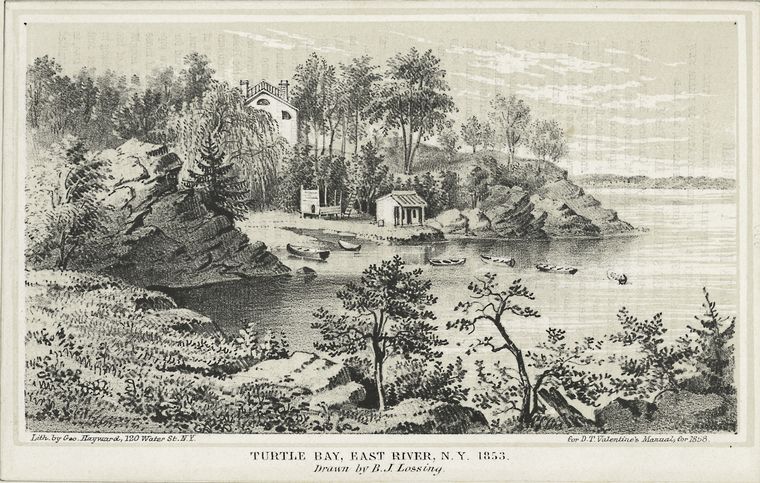

Turtle Bay originally emptied the natural stream coming from today’s Central Park Pond (located at the 59th Street and 5th Avenue entrance) into the East River. The United Nations headquarters in New York City today migrated to the former bay in the mid-20th century from its temporary convention center at Flushing Bay in Queens, which now is the building of the Queens Museum. By this time, the idyllic scene and natural resources at the bay were already razed and construction was underway to transform five industrial blocks of the city into the Headquarters. Le Corbusier along with Oscar Niemeyer, the leading advisors to the group of architects in the project, influenced for the complex to reflect the International Style of architecture. Today, the site is considered to be under jurisdiction of international grounds and stands very out of the way in its midtown context; water access is severed from the complex by the expressway and the buildings are erected in a slight depression within the landscape.

Map: Maps of farms commonly called the Blue book (1815), opacity:

-

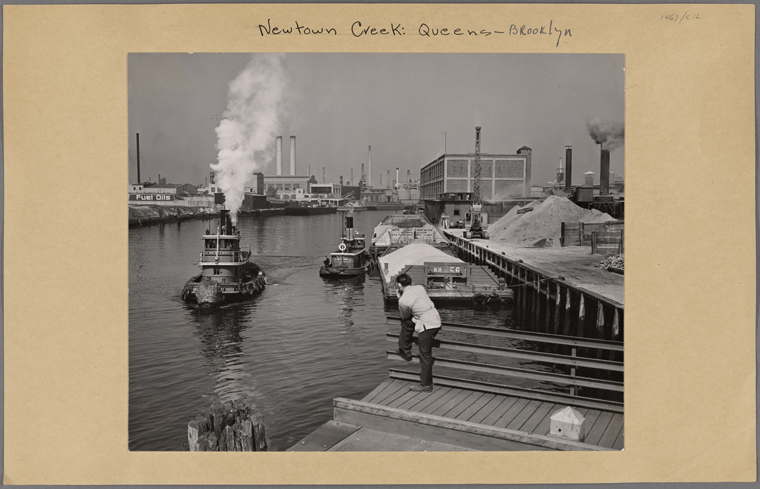

This charming and dynamic creek disappointingly has been corrupted by the city’s industrial zone like no other. In its most healthy state years ago, the creek would stream water into the East River from two divergent creeks located closer to the terminal inland. At the boundary between Brooklyn and Queens lies a cemetery belt separating the areas of Maspeth and Ridgewood from Bushwick where wetlands previously existed. Newtown Creek is notoriously and historically polluted with many of the factories and individual rubbish, including full animal corpses, throughout the years. It literally became the city’s trash septic. Controversial oil spills in recent decades has ruined the hydrology of the water up to such a critical point that millions of dollars in efforts, as well as the efforts of fervent activists in the neighborhood, has been spent to desperately replenish the Creek to some sort of functional state.

In the process of its restoration, the nature trail in Greenpoint along Newtown Creek seeks to console the situation of the Creek with its pungent past. The thin path outlines the periphery of the imposing wastewater treatment plant conducting a trail between the noxious creek water and plant’s storage eggs. The 360 view at the site provides no relief; crushing automobiles swinging in the air from large combine machines just across the water along with heaps of tires and empty lots all hug the nature trail with no familial affection. The nature walk’s attempt to attract the public to a healing waterfront is yet to be realized and someday may be activated to promote a larger scale intervention to consolidate all of Newtown Creek. And it’s not just the Creek’s shore that is changing: on the water, the North Brooklyn Boat Club hosts boaters from around the neighborhood and regularly leads water expeditions.

Map: Map of the consolidated city of Brooklyn (1865), opacity:

-

Under the green lawns and ball parks of McCarren Park in Greenpoint today lies the remains of sediment from which originated waterways flowing out of Brooklyn and into the East River years ago. In 1645 when the first settlers arrived and acquired the land from the Lenape, two streams could be found as crossroads in a landscape long removed by modern society. They converge at a local salt marsh exactly located at the site of McCarren Park today, which provided diverse ecological functions to the surrounding Brooklyn area and regulated the land’s natural hydrology. Bushwick Creek, in Dutch known as Boswijck or little town in the woods, was part of a larger shoreline condition that defined much of north Brooklyn’s egde at the East River and connected farmland production to markets in Manhattan.

As industrialization replaced many farmlands in Brooklyn, the waters were covered to provide as much usable land for new industry toward the middle of the 19th century. McCarren Park, commissioned in 1909, posted a strategic urban intervention of green space for northern Brooklyn which countered the highly industrialized neighborhood dominated by Astral Oil Works factories. Today, the area’s waterfront is a highly contested ground for stakeholders in land development. Rezoning in the city caused land values along the shore to increase. With luxury residential developments arising along the coast, it is crucial that the waterfront be open and accessible to all residents of the neighborhood. The Bushwick Inlet Park proposes to consolidate this edge and provide a naturalistic appearance of the shoreline including beaches and wetlands among its public programming spaces like a kayak launch. The last piece of waterfront was purchased by the city after heated negotiations of land purchasing which caused some delay in connecting and making accessible the north Brooklyn waterfront. Hopefully soon the fences guarding the space will be removed and the shoreline once again can be connected to the mainland in a meaningful and healthy way under the Bushwick Inlet Park plans.

Map: Map showing a part of Brooklyn (1855), opacity:

-

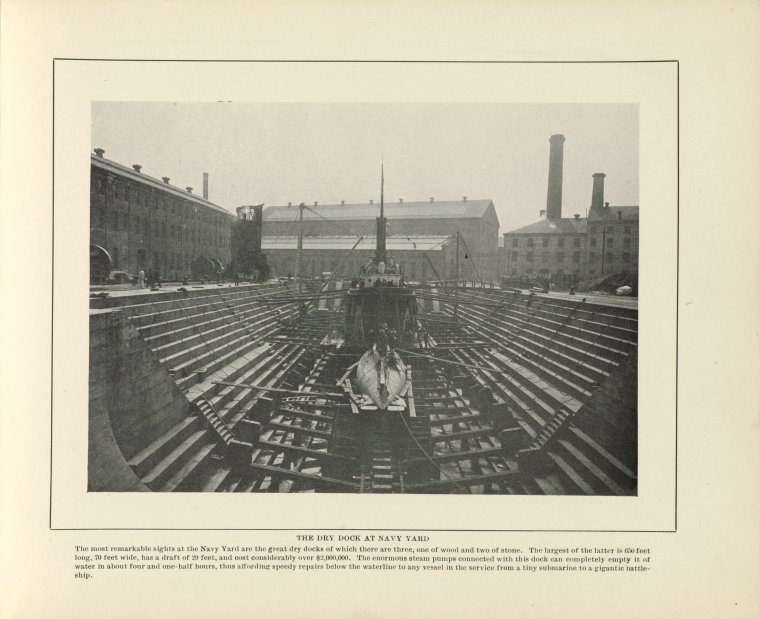

The site revels in industrial innovation from its first encounter with the colonial settlers that would populate the city’s growing independent district outside of lower Manhattan. The historical richness as first a natural bay, Dutch farmland, Revolutionary wartime prison barge, successful long-time active Navy Yard, 1970s & 80s urban blight, and today’s city industrial park reaches world wide scale in its many urban forms. Joris Jansen de Rapalje, Brooklyn’s first Walloon to inhabit the site, manages to till the land until British control in 1781 and whose farmland counts as one of the many plots which defined rural Brooklyn at that time. This character makes a reappearance in most of the early Dutch colony’s crucial negotiations to gain independence from the mother-country, including the settlers’s standoff with Dutch mayor Stuyvesant, whose farmland used to be just across the water in Manhattan where currently stands the Stuyvesant Town housing project. The original Walloon name, Waal-bogt, means bend in the harbor.

The natural habitat at the site, including a stream that is now forgotten under Wallabout Street, is cruelly taken under seige by British commanders during the Revolutionary War and is transformed into a prison barge. Thousands of captive people have died in the ships during the Revolution under horrific conditions and notoriously more people died on the artificial island in the Bay than in the all of the war’s battlefields. The Navy Yard continues its identity as a wartime post well into the 20th century, operating from 1801 to 1966 at the most crucial times in world history. Its dry dock allowed for the construction and repair of ships, which would allow ships to come into the bay and have river water drained out so that the sufficient repairs can be made. Contemporary shipbuilding sites at the time Brooklyn Navy Yard was active include the Bushwick Inlet which ceased production by 1889. Similar dry docks were founded on the west side of the East River on the Manhattan shoreline, mostly concentrated in today’s Lower East Side and more specifically at the edge of where Tompkins Square Park is today. The site was decommissioned as an active Navy Yard in 1966 along with many other military bases which caused many workers to be displaced and the site rapidly declined in industrial activity. The Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation controls the site from the 1980s onward and diversifies the traditional maritime industry to include other occupations such as roof top greenhouse agriculture and the nation’s largest film making studio outside of Hollywood. Many pre-civil wood frame houses are found in the neighborhood today, including Walt Whitman’s residence at the time he was completing Leaves of Grass, as well as the Pratt Institute campus.

Map: Map of the city of Brooklyn (1849), opacity:

-

Governor’s Island was actually the first stop for many of the first Dutch settlers in the New World. They tried to cultivate farmland, sawmills, and cattle here although the conditions were insufficient to continue these practices on the island. One can imagine the timidity many of the settlers would experience when facing the 1609 shoreline of the larger, more important island to the north. As the population increased on the little island, called Nooten Eylandt (Nutten Island) by the Dutch who went by the Lenape’s classification of the island, people slowly made the jump to Lower Manhattan via rowboats transporting their cattle and crops along with them. The shoreline of Lower Manhattan just beyond the original 70 acre island was an ideal location for many ships to dock as the waters reach depths enough for larger vessels to comfortably sit at the harbor. As Lower Manhattan shoreline’s grew, they took up more water area, thus changing the natural shoreline depth, often dramatizing depth for more and more ships to dock. Nutten Island remained an idyllic retreat for the Dutch settler’s governors as well as the future British commanders.

Map: Atlas of New York and vicinity (1868), opacity:

-

The beginning of the 19th Century piqued robust development for the Battery as well as the historic coastline of Lower Manhattan to grow into the body of today’s bustling metropolis. The factors that stimulated its growth depend on various pressures of either local, national, or international scale. Most fundamentally being the gateway to the new country, where the bustling metropolis of today originated from, the Battery’s expansions were provided to mediate and protect the new city’s identity as a port city. By this time, the European settlers have implemented piling strategies that reduced the waterfront to a binary condition, a hard city edge snapped to a swelling harbor to fulfill their needs of import/export. Larger moments of landmass acquisition include the southwest expansion of the Battery which was completed in 1811 by landfill. The point advanced in views of both the Hudson and East Rivers. In a different instance that reacted to a more international scale, the Battery expands during the War of 1812 to protect the Buttermilk Channel in the East River. The British never attacked Manhattan during this war, which in New England was regarded as President Madison’s War, a useless war that was brought on by the War Hawks legislature that was prevalent in America’s youth as a freshly independent country.

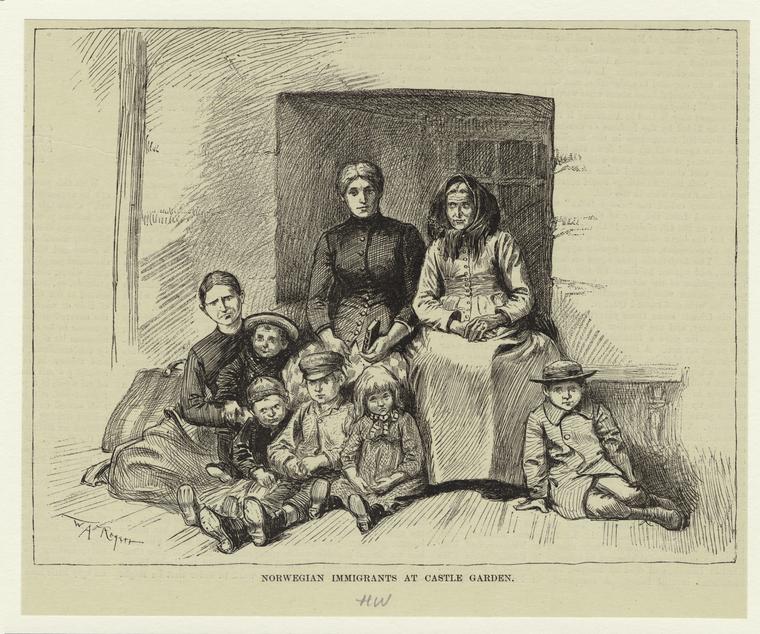

On a more local scale, the Battery adds a waterborne satellite to its commanding position on the island. Originally meant to provide an arsenal in times of battle, Castle Clinton is constructed from stone in 1807. The manmade island was connected to Manhattan by a wooden bridge and was never used for combat. In 1824 the fortress was converted to a gala space and the now Castle Garden hosts extravagant events for close to a quarter of a century. A huge fountain is installed in the interior of the space in 1843 which is at the time the city’s largest indoor concert hall. In 1855, the palace is joined by fill to Manhattan and given over to the state to become transformed into a temporary station where immigrants first arrive to the island.

In its original condition, as the Europeans would have found it in their first expeditions to the continent, the Battery extended in sandy beaches up to 34th Street on the West Side of Manhattan. The marine-water habitat at the Battery was very diverse because its bottom topography could have been inhabited by many different organisms, one of them being the oyster which famously formed extensive beds in the Harbor, naturally protecting the island from storm surge and rising tides. Because the Battery has been progressively constructed and reconstructed at the edge, thereby erasing the beach landscape and rich marine-water habitat, to fit the demands of the growing city, the coastline today is highly engineered to contain the lower part of the island and sustain its demanding accumulation of human intervention. Facing dramatic and fluctuating weather conditions throughout history in its various experiences of land usage, the Battery is defined by an innate resiliency that demands fortification whatever the time period. In its history as part of the new nation, the Battery has witnessed conditions as extreme as winters so cold that the New York Harbor froze over as during the Revolutionary War or as agreeable summers that fair well with its unique identity as Manhattan’s early beaches. Today the Battery is a key turning point in plans to retrofit a resiliency infrastructure along the coast of lower Manhattan. The Big U, designed by the Bjarke Ingels Group, encompasses a wide mile stretch of the historic waterfront in reaction to the unprecedented damage caused by Hurricane Sandy. The new development will wrap around the edge and install itself stealthily as a new urban program in already existing waterfront programming.

Map: Plan de New-York et des environs (1777), opacity:

-

Envisioned as a residential area for professionals working in the Financial District, Battery Park City sits on an artificial appendage of New York City and hosts mostly family dwellers who can afford the expensive high rise apartments there. Since the 1960s when the plans to build the new addition to the city emerge, many of the public space amenities Battery Park City projected at first were slowly taken up by buildings to house new residents. Located on the outside of the West Side Highway, Battery Park City includes specific destinations to attract the city into the town within the city, like NYC’s specialized public school Stuyvesant High School and the green spaces dispersed within the perimiter. The site was speculated in attempts to transform the dilapidating warehouses and piers that have before serviced the port city.

Realizing the new urban imaginary went through various installation periods that adjusted original plans as well as the relation of the materiality of the construction site to the surrounding community. From the beginning, the project encounters New York in a fiscally stagnant time and was determined to vitalize the Financial District. Proposals to hit the ground running in turn proved flat for some time. Debris and soil excavated from the World Trade Center construction phase composes Battery Park City’s foundation as well as rubbish landfill that collected over time when the plans to move forward with building plans stalled. Consequently, artists and artist collectives interevened at the landfill site, one such being Creative Time’s inaugural Art on the Beach that featured site specific installations by artists or Agnes Dennis’s Wheatfield — A Confrontation supported by the Public Art Fund which has produced stunning documentation of a gold wheatfield in downtown New York. The project actually cultivated wheat, successfully juxtaposing the rural environment that visually identifies with the non-urban but makes the relationship between both worlds more present and concrete in this altered landscape.

Map: Atlas of the city of New York (1885), opacity:

-

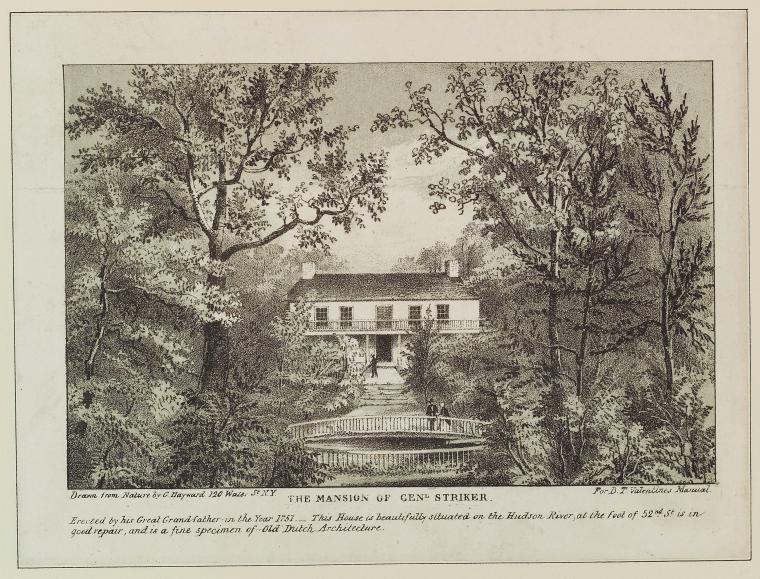

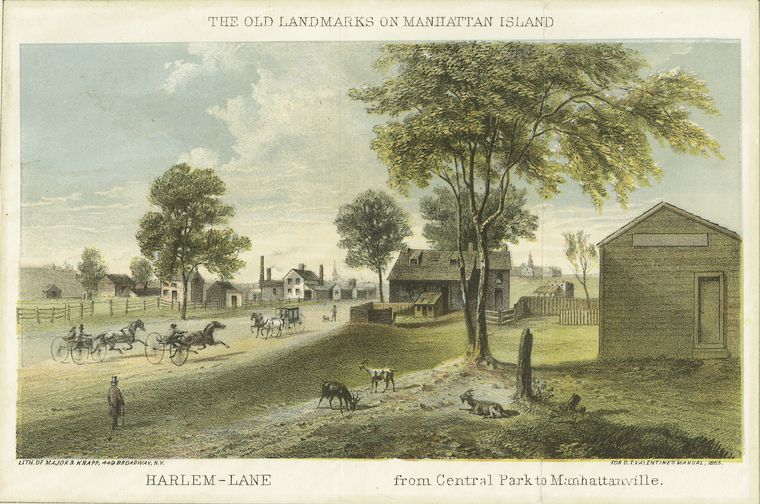

In New York City’s early colonial past, the Upper West Side of Manhattan rendered a wealthy suburban setting with small hamlets sprinkled conveniently along the island’s coastline. Stryker’s Bay was one of these settlements and centered itself around a small inlet that has since been filled in. Spanning the length of one subway stop on the 1 train, the sleepy town was comfortably situated between present day 86th Street and 96th Street along Bloomingdale Road, or today’s Broadway. The bay had an intimate waterfront public life and hosted joyful small town affairs at the Stryker’s Bay Tavern. A ferry transported people from Stryker’s manicured farmlands and picket-fences along the Hudson River to a bustling downtown area teeming with new businesses and modern city developments. The majority of these West Side towns took advantage of the undisturbed natural topography of Manhattan, although many, like Harsenville, Carmansville, and Manhattanville, used it to their advantage, either exploiting land for industrial use, farmland, or institutional landmarking.

-

Tubby Hook was once an awesome natural feature of the Manhattan coastline and the rural charm of Manhattanville was enhanced by the grandeur of the Hudson and the Palisades just across the river in New Jersey. A subject of many artistic expressions, particularly in the Hudson River School of painting, Tubby Hook, along with Fort Tryon Park and the surrounding area, including the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb which is situated on present day Columbia University campus, was rendered as one of the last untouched habitats of the island before the grid influenced their divisions.

Many of the early Westside hamlets were slowly being taken over by development in the late 19th Century. The more romantic rural settings were decimated by the repetitive grid system which paradoxically complicated the seeming order of the nature present to descriptions of the natural landscape of early Manhattan. However, the hamlets in themselves can be seen as the seeds of urbanization itself and it would be blinding to want to preserve the idyllic quality of Nature when its bound to human intervention at any rate. The illusive Tubby Hook, a detail in the city’s history but a great promontory of the physical coastline, grounds the experience of the destruction of the natural habitat when it is pummeled to the ground literally to provide for landfill and expansion material.

Down there, on old Manhattan,

Where land-sharks breed and fatten,

They’ve wiped out Tubby Hook.

That famous promontory,

Renowned in song and story,

Which time nor tempest shook,

Whose name for aye had been good,

Stands newly christened “Inwood”

And branded with the shame

Of some old rogue who passes

By dint of aliases,

Afraid of his own name!

William Allen Butler, 1886